We know that when you engage with a financial advisor, you not only commit your finances to a long term strategy, but also your emotions. We can easily and objectively measure financial performance: Did you achieve your savings goal? Are you on track to retire comfortably? However, measuring and managing your emotional performance is, well, an emotional affair.

Although there is no universally accepted definition for emotion, it may be thought of as a mental state that arises spontaneously rather than through conscious effort. When your team scores the winning points 5 seconds before the end of the game, you don’t sit and think about how you are going to react. You just simply jump up and high-five everyone within a two meter radius.

As your financial advisors, we understand that you are wired to make emotional decisions which will be detrimental to your financial performance. This is a fact, and no matter how emotionally in-tune or emotionally intelligent you are, you are not above the irrationality that comes with making decisions about your wealth.

As an interesting exercise, let’s go through five of the most common emotional biases to see how many you can relate to:

Loss Aversion Bias – You would much rather prefer avoiding any losses as opposed to achieving gains. As an example: you are asked if you would like to play a game. You can freely choose if you would like to play or not. The game is based on the flip of a coin. You win R200 for heads, but you pay in R100 for tails. Most people would say ‘no thanks’, as the idea of having to pay R 100 for nothing gained does not go down well.

Overconfidence Bias – You demonstrate unwarranted faith in your own abilities, often based on past experiences. You might have bought your first house at the absolute bottom of the market, and made a good profit when selling a short while later. This good outcome (which may or may not have been due to luck or skill), creates a sense of overconfidence when buying your next house, where you suddenly feel like an expert and over-estimate your ability to do the same in the future.

Self-Control Bias – We see this one every single day. We prefer short term benefits over long term benefits, as there is no immediate tangible satisfaction today. You need to save for your retirement, but life is (apparently) more fun in a new car, and you defer saving for another year or two. No self-control.

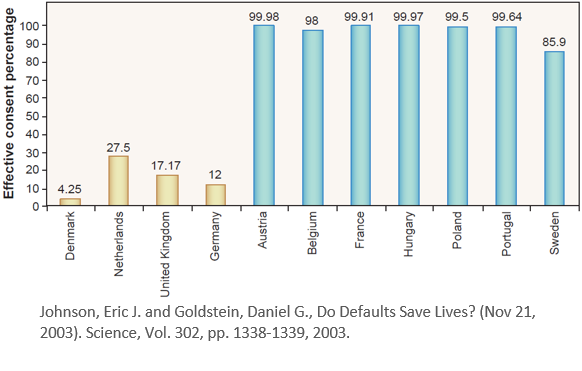

Status Quo Bias – People are inherently lazy, with decisions often deferred indefinitely if they do not feel immediate consequences. The prime example of this is the following comparison:

Above, European countries are graphed by organ donation rates. The countries in gold clearly have lower rates of organ donation than the ones in blue. The reason for the difference? The countries in blue rely on people to be lazy, and set the default option as being an organ donor for all citizens. This ensures that people have to make an effort to change their organ donor status. As individual investors we prefer keeping things the way they are, and resist change purely for the perceived effort in making changes.

Endowment Bias – This is when you value an asset more than it is worth, purely because you are the owner of it. Think about your long-time family house in which all the grandchildren were brought up. The price you are willing to sell it for is likely much higher than what you would pay for a similar house if you had to buy one today.

By identifying these and other biases which could negatively affect your financial decisions as you go through different stages of life, we are able to guide you through the difficult times and continuously advise you to stay the course, no matter how emotional it may become.